This page last revised 05 September 2018 -- S.M.Gon III -- THIS IS AN ARCHIVE WEBSITE. Please see the current projects of The Nature Conservancy of Hawaiʻi

Introduction

Ecoregion

Conservation Targets

Viability

Goals

Portfolio

TNC Action Sites

Threats

Strategies

Acknowledgements

▫

Tables

Maps & Figures

CPT Database

Appendices

Glossary

Sources

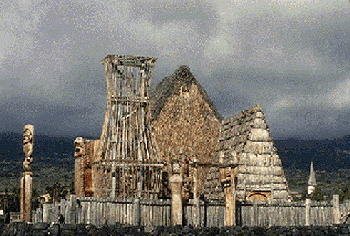

A modern resurgence of Hawaiian cultural practice and values includes a growing appreciation of the native species and ecosystems that made it all possible.

In 2010, the Hawaiʻi Conservation Alliance of 25 of the leading agencies and organizations in conservation, ratified a position paper affirming the value of Hawaiian Culture in Conservation.

Hawaiian Culture

and Conservation

Introduction

Such an approach would be grounded in ancient Hawaiian traditions, but relevant to our times, responsible to Hawaiian culture as well as scientific rigor in order to protect Hawaii’s native culture and natural heritage through active stewardship, research, and education.

Connections of people to place

kuahiwi kaulana o O‘ahu

famous mountain of O‘ahu

This saying speaks with pride about the famous mountain of O‘ahu, its highest peak, Ka‘ala (above), regarded as sacred and pristine. It is not surprising that Ka‘ala still confers that sense of deep awe when visited today, and it is clear that we can share and appreciate ancient values even in modern times.

Inclusive relationships

It

boils down to establishing a relationship between people and their lands. For native Hawaiians, these islands are the “one

hānau” the “birth sands” and so it is a responsibility to know your lands and care for them. For most conservation biologists who work here, a similar relationship grows

out of long-term, intimate knowledge of the species and systems in which they work.

Hawaiian

material culture relied upon native species and ecosystems.

Hawaiian

material culture relied upon native species and ecosystems.

Thus, the unique biodiversity of the Hawaiian ecoregion valued greatly by evolutionary biologists worldwide also generated an equally rich cultural system in the isolated, pre-western indigenous Hawaiian society that developed within it. Native species carry great cultural significance and value that can and should be wielded as a powerful basis and justification for conservation.

Lei o manō (sharktooth weapon) and ki‘i

hulu (feather god image) are material examples of biocultural resources.

In modern Hawai‘i it is increasingly difficult to connect meaningfully with the natural world.

Hawaiian tradition tells of snails singing and whistling in the upland forests.

Reciprocal responsibility

He ali‘i nō ka ‘āina, ke kauwā wale ke kanaka

The land is the chief, the people merely servants

Pueo (Hawaiian owl) is an ‘aumakua to many Hawaiian families. The red blossom of the lehua is the kinolau of the volcano goddess Pele.

Plants and animals as elders

It all boils down to motivated, responsible action, informed by knowledge both traditional and academic, and driven by a caring relationship that views elements of the natural world as kin...

Recent flowering of both biocultural approaches to conservation and community based co-management of natural resources in Hawaiʻi means that the cultural underpinnings described here are being expressed more and more as a viable tool for conservation.

Kapu and Noa

Human use of natural resources in ancient Hawai‘i were based upon religious restrictions (kapu) that maintained proper balance (lōkahi) at multiple levels, between people and resources. Abuse of resources under kapu was punished harshly, typically by death of the violator, lest doom come to all. When balance was achieved, kapu could be lifted (noa) and resources used with care.

Integration of the natural world with spirituality brings stewardship into the realm of moral obligation. Reinsertion of humans into the native landscape is something that extends beyond the typical bounds of western science. Relationships that involve the spiritual side of human existence tend to be avoided by western science, but are sought and embraced by Hawaiian culture.

Hawaiian Science

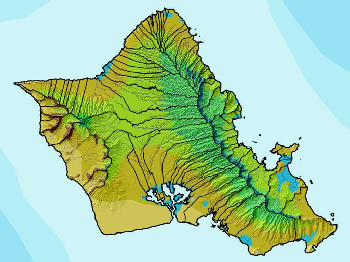

Ultimately, Hawaiian knowledge was empirical, based on repeated observations of patterns in the universe. Such patterns extended to entire islands, seen in the traditional land management system, wherein an island was divided into natural watersheds (ahupua‘a) extending from mountaintop to deep sea, ensuring access to the full range of natural resources for people living within an ahupua‘a.

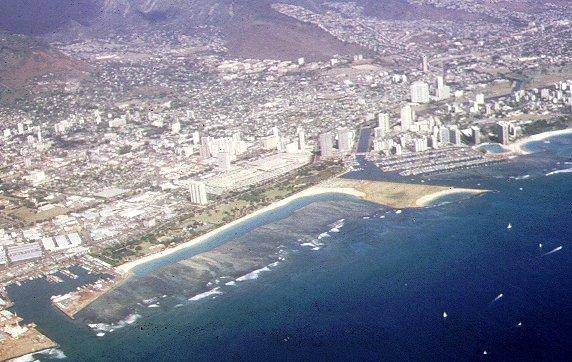

Ahupua‘a

boundaries

of the Island of O‘ahu (black) show remarkable optimization of access to ecological system resources.

Ahupua‘a

boundaries

of the Island of O‘ahu (black) show remarkable optimization of access to ecological system resources.

Hawaiian science was empirical, experimental, repeatable, promulgated via stories and chants, tested, adaptive, and thus of great value to modern conservation.