This page last revised 05 September 2018 -- S.M.Gon III -- THIS IS AN ARCHIVE WEBSITE. Please see the current projects of The Nature Conservancy of Hawaiʻi

Introduction

Ecoregion

Conservation Targets

Viability

Goals

Portfolio

TNC Action Sites

Threats

Strategies

Acknowledgements

▫

Tables

Maps & Figures

CPT Database

Appendices

Glossary

Sources

Some of the world's wettest regions lie in the ecoregion's montane systems

Some of the world's wettest regions lie in the ecoregion's montane systemsEcoregion Description

Location and context

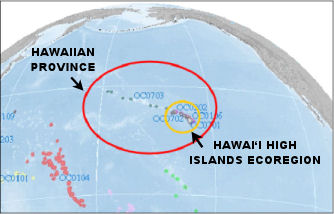

The Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregion lies in the north central

Boundary

The Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregion Boundary is defined by the TNC/NatureServe National Ecoregional Map. It is a modification of Bailey's Ecoregions of theThe Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregion contains three major habitat types:

(continued next column)

Physiography

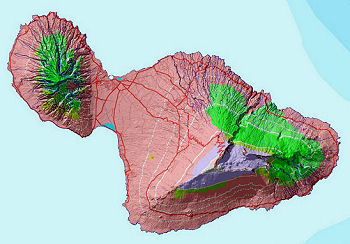

The Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregion is marked by a very wide range of local physiographic settings. These include fresh massive volcanic shields and cinderlands reaching over 4000 m (13,000 ft) elevation; eroded, faceted topographies on older islands; high sea cliffs (ca 900 m [3,000 ft] in height); raised coral plains; and amphitheater-headed valley/ridge systems with alluvial/colluvial bottoms. Numerous freshwater stream systems are found primarily on the older, eroded islands, but also on the wet, windward slopes of even the youngest island, Hawai‘i (Juvik & Juvik 1998).

Climate

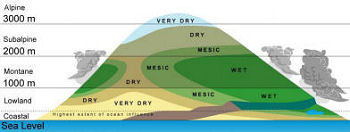

The general climate is tropical/subtropical, but with combinations of elevation and orographic rainfall patterns that yield extremely wet (>1000 cm [>400 inches] annual rainfall) to extremely dry (<25cm [<10inches] annual rainfall) settings within a short distance of each other (<40km [25 miles]), topped by alpine deserts on the youngest and highest islands (Giambelluca & Schroeder 1998). All but two of the eight main Hawaiian Islands rise to montane elevations (>1000 m [>3000 ft]). The general patterns of climatic variation found on the largest of theThe Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregion (right, yellow oval) lies within the Hawaiian Province (red oval), in the Oceanian Biogeographic Realm.

High island orographic climate results in both extremes of wet and dry, while broad elevational reach yields tropical hot to alpine temperature regimes.(Click on the image above to view a larger version).

Hawai‘i includes more endangered species than any other state of the U.S.

Biodiversity Significance

The Hawaiian High Islands Ecoregion is marked by extremely high endemism (e.g., ~90% endemism of native flowering plants; >98% endemism of native terrestrial invertebrates) (Loope 1999). An estimated 15,000 endemic species occur in the ecoregion (Eldredge & Evenhuis 2003). The Hawaiian flora of about 1,200 vascular plant species is disharmonic, that is, lacking many genera and families that typically mark tropical island systems (Sohmer & Gon 1995). Rare and endangered taxa, including endangered plants, forest birds, and land snails comprise >25% of the fauna. Hawai‘i includes more endangered species than any other state in the

In addition to species, all but ahandful of the approximately 150 described terrestrial native natural communities are endemic. Vegetation includes grasslands, shrublands, woodlands,and forests in lowland, submontane, montane, subalpine, and alpine settings (Pratt & Gon 1998). Hawai‘i supports more Holdridge life form categories than any other ecoregion known (Tosi et al 2001, Ewell 2004). Lists of the natural communities and rare/endangered species of the ecoregion can be found in the appendices.

Endemism

Biological diversity in the

Because of all of these island-level endemics, fewer than half the flowering plant taxa (409) show multi-island distributions. Fewer than 150 can be found on all six of the higher main islands. The situation is even more pronounced among invertebrates, which comprise the majority of species-level diversity of the ecoregion, and show remarkable diversification and geographic endemism even within a single island setting.

Multiple examples of ecological systems across the archipelago are clearly required to adequately represent species level biological diversity. For broad-scale planning, a geographic stratification approach is needed, and was developed as part of this 2nd interation plan.

Significant portions of the lowlands have been displaced by human development.

Bringing active management to priority land- scapes is the overall goal.

Alien species, such as feral ungulates, are a prevailing threat to native ecosystems in Hawai‘i

Strong connections between the natural world and indigenous Hawaiian culture can aid conservation.

Land Use Patterns

Human residence and extractive land uses are largely concentrated below 600 m (2000feet) elevation. Land uses include high-density urban, residential, agricultural, grazing, and lands dedicated to military training. Higher elevation areas are more natural, are largely zoned for conservation, and include many areas in protective status such as national parks, natural area reserves, forest reserves, preserves, and refuges. Upland watersheds on most of the main islands are included in informal public-private cooperative management areas called watershed partnerships, managed for maintenance and management of forested watershed. Over 30% of the ecoregion is privately-owned, 29% in state holdings, approximately 8% in federal lands, and the remainder in county and other tenure. These proportions also apply to the biologically intact island interiors, necessitating state, federal, and private participation in comprehensive conservation efforts (Hawai‘i GAP 2005).

Continue to Ecoregional Conservation Targets

Socioeconomic Setting

The general setting for conservation in Hawai‘i is relatively stable. There is none of the sometimes violent instability that plagues many of the world's tropical biodiversity hotspots.

Large tracts of former agricultural lands are being converted into residential areas or are left fallow, often creating vectors for weed invasions or wildfire. Rapidly rising land and property costs (among the highest in the U.S.) have created a high cost of living, exacerbated by our geographic isolation and need to import many/most necessities (food, shelter, clothing, fuel). Economically depressed rural areas occur on all islands where subsistence hunting/fishing persists. Business centers can be found in

Government agencies and the public recognize that natural areas and watersheds are important for quality of life. Strong connections between the natural world and indigenous Hawaiian culture hold great potential for conservation. However, conservation and public land management are severely under-funded and a multiple use mandate conflicts with management actions focused on biodiversity conservation. High land costs make conservation acquisition a very expensive strategy, and overall high costs of living apply to the costs of essential management actions.